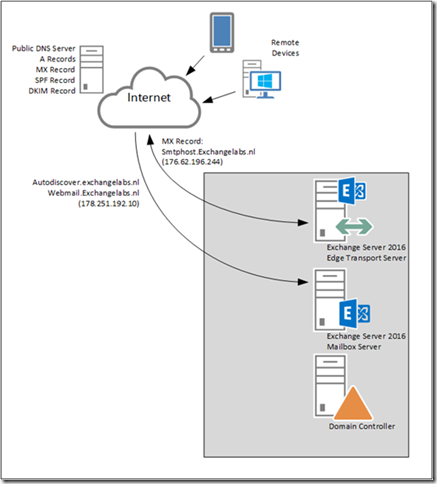

My previous blogpost was about DANE and discussed how DANE can be used to make TLS negotiations between mailservers more secure. Another topic in this area is MTA-STS. MTA-STS stands for Message Transfer Server – Strict Transport Security and MTA-STS is a mechanism to enforce the use of TLS and the use of a valid 3rd party server certificate.

MTA-STS, DNS and Policies

When an MTA-STS capable servers wants to send an email, it first retrieves the MX record for the recipient domain. The second step is that the sending server check for an MTA-STS record in DNS. This record looks like:

_mta-sts.exchangelabs.nl. IN TXT "v=STSv1; id=202306242147;"The id is an identifier and defines the version of the MTA-STS record when changes are made to the MTA-STS record. A good practice is to create an identifier based on the date and time of the last change. In this example, it is June 24, 2023 at 9:47pm.

The next step is that the sending servers looks for a policy. This policy is not stored in DNS, but on a website. The URL for this policy looks like: https://mta-sts.exchangelabs.nl/.well-known/mta-sts.txt. The subdomain mta-sts, the filename mta-sts.txt and the directory .well-known (including the dot) directory are mandatory for the MTA-STS policy. It must also be secured using a valid 3rd party server certificate.

The MTA-STS policy will look something like:

version: STSv1

mode: enforce

mx: smtphost.exchangelabs.nl

mx: *.mail.protection.outlook.com

max_age: 604800Note. If you have configured DANE for inbound email in Exchange Online, your MX record should be something like Exchangelabs-nl.y-v1.mx.microsoft.

The MTA-STS policy is structured as follows:

- Version identifies the version of MTA-STS but must always be STSv1 (for now at least).

- Mode defines how the policy must be applied:

- Enforce: Sending MTAs MUST NOT deliver the message to hosts that fail MX matching or certificate validation or that do not support STARTTLS.

- Testing: Sending MTAs that also implement the TLSRPT (TLS Reporting) specification [RFC8460] send a report indicating policy application failures (as long as TLSRPT is also implemented by the recipient domain); in any case, messages maybe delivered as though there were no MTA-STS validation failure.

- None: In this mode, Sending MTAs should treat the Policy Domain as though it does not have any active policy.

- MX defines all MX records in use by the recipient domain. This can be one entry, but it can hold multiple MX records, each on a separate line as shown in the policy above.

- Max_age defines the time (in seconds) that the MTA-STS policy can be cached by a mail server. In this example, the policy is cached for 604800 seconds, which equals to 1 week. When a sending server must send a new email within a week, the policy is still cached. After checking the MX record the server retrieves the TXT record from DNS (as explained in the second step above) and when the identifier has not changed it uses the policy that is cached. If the identifies has changed within the lifetime of the cached policy, a new policy is downloaded.

So, in my example an MTA-STS capable mail server will check the MTA-STS policy and only connects to my mail server using TLS 1.2 (this is enforced with MTA-STS when mode is set to ‘enforce’) and only when a certificate that matches the FQDN is used. When authentication fails for an entry, the sending server continues with the next line in the policy, in my example with the MX record pointing to Exchange Online.

An interesting option in MTA-STS is reporting. DMARC has a reporting function as well, but reports are only sent by receiving domains. Reporting in MTA-STS is performed daily by sending mail servers that supports MTA-STS and TLS-RPT.

To configure the reporting functionality, create a mailbox in Exchange 2019 or Exchange Online and assign it an email address like TLSReports@Exchangelabs.nl. The next step is to configure the following DNS TXT record:

_smtp._tls.exchangelabs.nl. 3600 IN TXT v=TLSRPTv1;rua=mailto:TLSReports@exchangelabs.nl

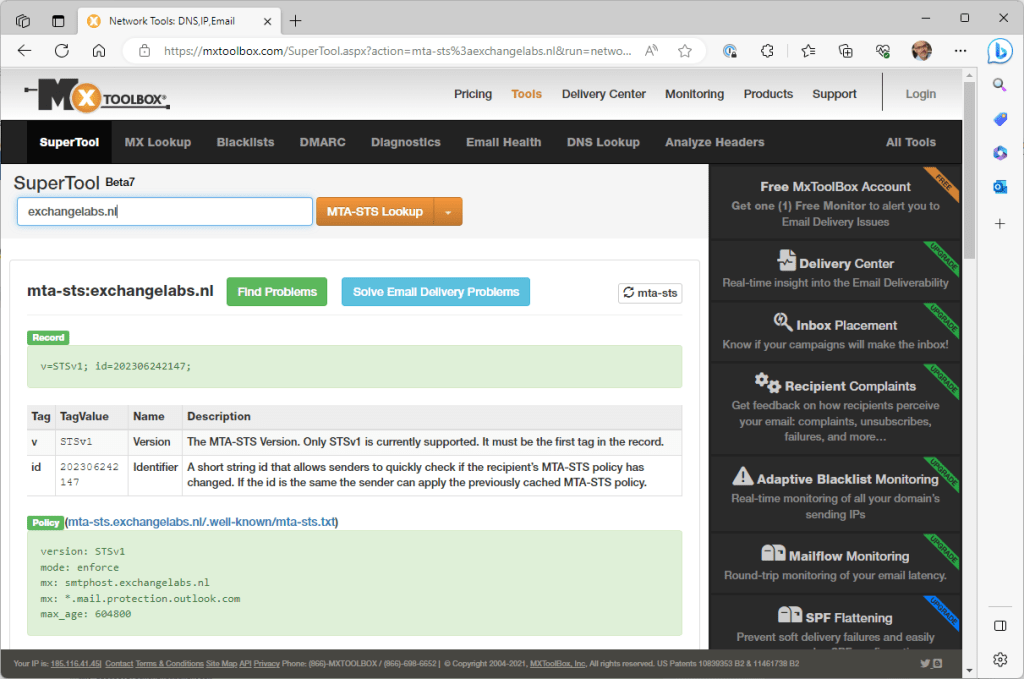

There are several online tools available for checking the MTS-STS record. Just like in my other blogs, I often use MXToolbox to check for DNS records as shown in the following screenshot:

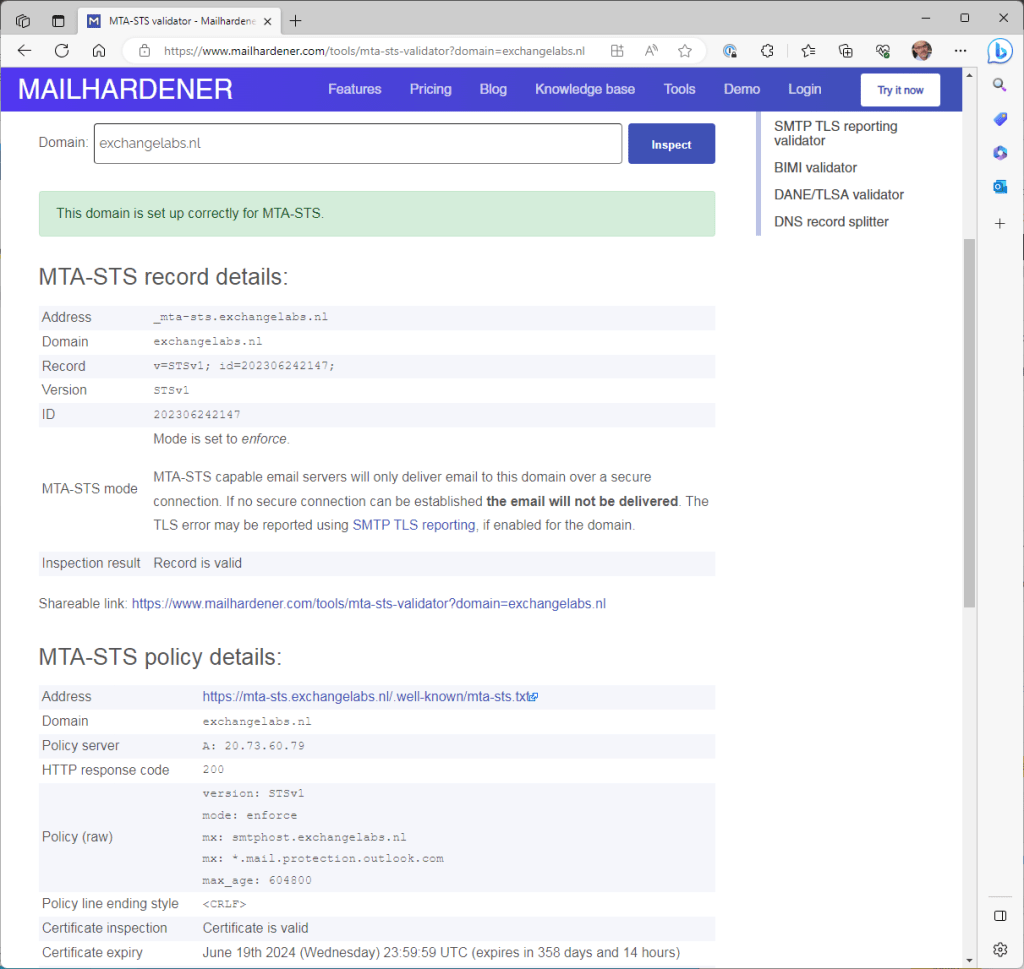

As with the DANE checks, the mailhardener site (https://www.mailhardener.com/tools/mta-sts-validator) can also be used to check MTA-STS records as shown in the following screenshot:

When you check the IIS logs of the webserver where the mta-sts.txt file is stored, you can see which servers are using MTA-STS:

2023-07-11 08:29:59 172.16.1.4 GET /.well-known/mta-sts.txt - 443 - 74.125.217.68 Google-SMTP-STS - 200 0 0 119

2023-07-11 13:54:51 172.16.1.4 GET /.well-known/mta-sts.txt - 443 - 104.47.11.254 - - 200 0 0 62

2023-07-11 14:13:37 172.16.1.4 GET /.well-known/mta-sts.txt - 443 - 77.238.178.114 AHC/2.1 - 200 0 0 20The first one is obvious, the second line is a Microsoft IP address, the third line is a Yahoo IP address. So, Google, Microsoft and Yahoo are using MTA-STS when sending email.

MTA-STS versus DANE

MTA-STS and DANE share a common concept, that is to secure the (initial) communication between mail servers. The ‘problem’ with DANE is that is relies on DNSSEC and the global roll-out of DNSSEC is very slow (to put it mildly).

MTA-STS was developed to overcome the slow roll-out of DNSSEC (since it does not use DNSSEC of course). MTA-STS can be seen as a ‘light-weight’ version of DANE and it will be sufficient for most customers.

And how about Exchange?

Just like with DANE, the ugly part is that Exchange 2019 does not support MTA-STS. You can configure the MTA-STS record in DNS and the policy on a website so that MTA-STS capable servers use your Exchange 2019 server safely. But for sent messages by Exchange 2019, MTA-STS is a no-go, it does not support it and most likely will never do.

Exchange Online on the other hand does support MTA-STS (since the beginning of 2022) for both inbound and outbound messages. The only thing you must do to enable it for inbound messages is create the TXT record in DNS and create and publish the MTA-STS policy.

Edited on July 11, 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.